See The Ajrakh Block Printed Textiles

Block printed cotton cloth is one of India’s great technological breakthroughs. The creation of vibrant, colourfast, cotton printing may date back as far as four millennia. There is a tantalizing similarity between the trefoil garment pattern found on a figurine recovered at Mohenjo Daro and a cloud pattern still used by block print artists working in western India today.

Archeological evidence suggests that for thousands of years Ajrakh artisans were located near the banks of the Indus river. The river provided both a site for washing cloth and the water needed to grow indigo. With the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, artisan communities were tragically separated. Today the craft continues with variations on both sides of the border. Indian artisans are centred in Gujarat with most communities living in the Kuchchh desert.

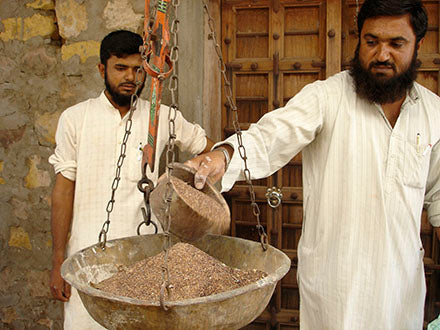

Bales of cotton yardage are torn by hand into 10 meter lengths and folded to permit easy handling. The raw cotton is scoured with soda ash, sometimes it is soaked overnight, sometimes it is steamed for an entire day. The cloth is washed and rinsed: if washed in the river it is thrashed against flat stones; if it is washed in an artisan’s cistern (increasingly necessary with falling water tables) it is beaten with wooden paddles. The washed cloth is next treated with a solution of cow or camel dung, often with castor oil added. It is washed and thrashed again. In Sindh one variation documented by Noorjihan Bilgrami requires Ajrakh artisans to treat the cloth with castor oil and soda ash before wrapping it in sacking and letting it cure for between five and ten days. After this, in what must have been the most delightfully aromatic step in the process, cloth was soaked in a mixture of tamarisk gall, dried lemon, castor oil, and molasses. Artisans in India do not cure the cloth this way, instead they put it through a myrobalan bath, and thus introduced tannin and also a light yellow colour to the fabric.

Two weeks can be spent preparing the cloth before printing even begins. To appreciate how such complexity evolved it is important to realize that colour on cloth is not achieved through printing just a dye. The artisan is not using pigments. Rather, three elements are deployed in various combinations: tannins, mordants, and dyes. Tannins can be either coloured or colourless, mordants can be mineral salts such as alum (but a copper mordant is also occasionally used); dyes can come from a wide range of sources including vegetable (madder, pomegranate, tumeric, and so on) or insect sources (lac for example) or minerals (iron salts such as ferrous sulphate and ferrous acetate), and some dyes, such as indigo, behave in a way that puts them in a class all their own. Altering the pH of the dye process or the temperature of a dyevat will shift colours into colder or warmer shades.

Printing techniques are further complicated by the fact that dyes, mordants, and tannins must be modified so they can be delivered onto cloth through the use of wooden blocks. Finally, they need to be stabilized in order to remain effective even while the entire cloth is immersion dyed—often at temperatures close to boiling. All this helps to explain how printing processes became more and more elaborate over time and how, like an architectural masterpiece, each step fits perfectly with preceding steps and anticipates the final steps before washing. Indian blockprint artisans are masters of a complex patterning calculus.

The intricate designs demand great focus and commitment. The marvel of a two sided ajrak, with the pattern registered and printed once on the front and reversed on the back, is a testament to the precision and capability of the creative spirit.

Maiwa actively seeks to support ajrakh artisans who live and work in the Kutch desert. We incorporate a large amount of their textiles in our bedding and clothing lines. While we assist in procurement of raw materials, maintaining high standards of quality, and product finishing, designs remain the realm of the craftperson.